Starting a company is messy. It involves pivoting, scrubbing toilets (literally, in some cases), and handing out frozen water bottles to strangers. In a lecture for Y Combinator, Adora Cheung, founder of Homejoy, shares the gritty reality of going from zero users to many.

Whether you are a student or working a job, the first rule is "compressed time." You cannot build a startup working two hours a day scattered throughout the week; the context switching kills focus. You need one or two full days straight per week to immerse yourself in the problem.

Here is the step-by-step breakdown of how to build, launch, and grow, using real-world lessons from the trenches.

1. The "Novice" Trap vs. Real Validation

Many founders fall into a vicious cycle. They have a "great idea," keep it secret, build in isolation, and launch on a platform like TechCrunch expecting instant success. When users don’t stick around, they give up. Adora admits she fell into this exact trap during her time at YC in 2010. She didn't even launch a product during the program.

To avoid this, you must validate the problem before building.

Adora learned this the hard way. In 2009, she and her brother started "Pathjoy," a platform for life coaches and therapists. They wanted to make people happy and build a big company, but there was a glaring problem: they weren’t the target audience. They realized that "life coaches and therapists are just not people we would use ourselves." They had spent a year building a solution for a problem they didn't have and weren't passionate about.

2. Become the Expert (Get Your Hands Dirty)

Once you have a problem you care about, don't just disrupt an industry from the outside. Immerse yourself in it. You need to become a "cog in the machine" for a month or two to understand the inefficiencies.

When pivoting to Homejoy, Adora didn’t just write code. She cleaned houses. She and her co-founder quickly realized they were "very bad cleaners," and buying books on the subject didn't help. As Adora notes, reading about cleaning is like reading about basketball. You don’t get better until you actually throw the ball into the hoop.

To truly learn, she got professional training and took a job at a local cleaning company. This gave her the "golden nuggets" of insight she needed. She saw firsthand how inefficiently local companies handled booking and scheduling, which explained why they couldn't scale. She learned exactly what to automate by doing the work herself.

This obsession should extend to your market research, too. You must know everything your competitors are doing. Adora didn't just Google competitors; she clicked on every search result from 1 to 1,000. She read the S-1 filings and quarterly financials of public competitors and listened to their earnings calls to find the hidden inefficiencies.

3. The MVP and "Simple" Positioning

When you start building your Minimum Viable Product (MVP), build the smallest feature set needed to solve the core problem. But just as importantly, you need to explain it simply.

Homejoy struggled with this initially. They described the service as an "online platform for home services" where you could choose various options. It was a boring, complex paragraph, and users tuned out.

They fixed this by changing their positioning to a simple functional benefit: "Get your place clean for $20 an hour." Suddenly, everyone understood the value proposition, and users started coming in the door.

4. The Hustle: How to Get Your First Users

Your first users will likely be your parents and friends. But your mom will always be proud of you (and lie to you), and your friends just want to support you. You need strangers. When online communities and mailing lists aren't enough, you have to get offline and hustle.

Adora went to street fairs in Mountain View to chase down customers, but most people said no. Then, on a hot, humid day, she noticed everyone gravitating toward food and drinks. She bought water bottles, froze them, and handed them out for free. She basically "guilt-tripped" people into booking a cleaning. Surprisingly, the retention of these "guilt-tripped" users was actually decent.

Another YC startup focused on shipping used a similar tactic.Instead of buying ads, they went to the U.S. Post Office, found people standing in line holding packages, and pulled them out of line to pitch them directly. They said, "Use our product, we'll ship it for you."

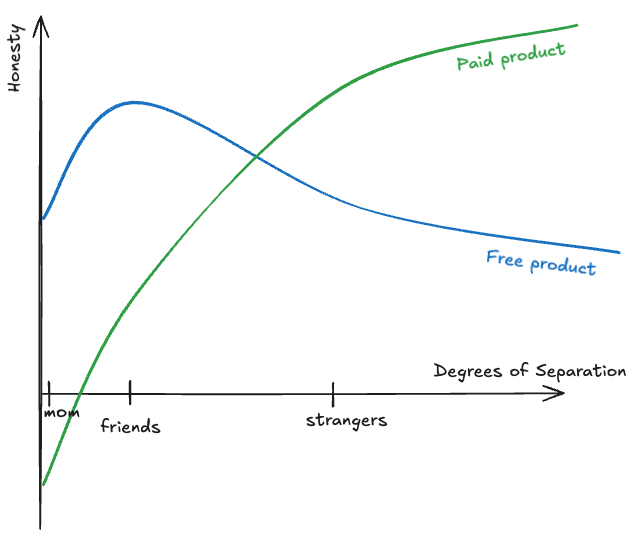

5. Talking to Users: The Honesty Curve

You need feedback, but don't treat user interviews like an inquisition in a laboratory. Make it a conversation. Adora found that taking users out for drinks or coffee made them comfortable enough to be honest.

When listening to feedback, be aware of the Honesty Curve:

- Mom: Lies to protect your feelings.

- Friends: Mostly honest, but biased toward support.

- Random Free Users: Don't care enough to give deep feedback.

- Random Paid Users: The gold standard. If a stranger pays for your product and hates it, they will tell you exactly why because it’s "money out the door."

6. Process: Manual Before Automation

Do not automate a process until you have done it manually enough times to understand it. If you automate too early, you lose the ability to iterate quickly.

At Homejoy, they initially interviewed every cleaner in person or over the phone. It was a grind with a 3-5% acceptance rate. However, by asking questions manually, they learned which specific questions were indicators of a "good" or "bad" cleaner. Only after learning this data did they build an online application form to automate the process.

Temporary Brokenness > Permanent Paralysis: Founders often obsess over "edge cases" (what if this rare thing happens?). Adora advises: Perfection is irrelevant. Build for the "Generic Case" (the 90% happy path).

- The Rule: Let the product be "broken" for the edge cases.

- The Reason: If you try to fix every edge case before launching, you suffer "Permanent Paralysis" and never ship. Fix the edge cases only when the volume becomes unmanageable

The Frankenstein Warning: Don't build every feature users ask for. If you do, you get a "Frankenstein" product. Dig deeper: usually, when a user asks for a feature, they are actually saying, "I have a problem you haven't solved yet".

7. Growth: Focus and Economics

When you are small, don't try five growth channels at once. Pick one (e.g., Facebook ads, referral programs, PR), execute on it for a week, and if it fails, move on. If it works, double down.

Homejoy tried to buy users via Google Ads early on, but they failed. Why? Established competitors like Merry Maids had much higher budgets and made more money per job, so they could afford a higher Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC). Homejoy had to find other channels until their economics improved.

As you grow, you need to track retention through Cohort Analysis:

- Bad Growth: You acquire 100 users in March, but by April, 0% remain.

- Sticky Growth: You acquire 100 users, and over time the curve flattens (e.g., 20% stay forever).

Crucially, ensure your Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) is higher than your Cost of Acquisition (CAC). For example, a user in Nashville might have a much higher CLV than a user in Czechoslovakia, so you can't spend the same amount acquiring them.

8. The Art of the Pivot

Homejoy was Adora’s 13th idea. How do you know when to move on? If you are working hard and executing fully, but see no growth for 3 to 4 weeks, you are fundamentally doing something wrong. You should have an optimistic growth plan (1 user, then 2, then 4). If the line is flat despite your best efforts, it's time to pivot.

However, sometimes the problem is just "switching costs." If users already have a solution (like a regular cleaner), switching is hard. You need a "wedge."

Homejoy found that people with regular cleaners wouldn't switch until their cleaner cancelled or they had a sudden need, such as a party the next day. Homejoy offered next-day availability to capture this demand. Once the user tried the service to solve that immediate emergency, Homejoy could hook them with features like online payment and easy scheduling.

Questions:

What do you mean by, "I have a problem you haven't solved yet"?

1. Users are bad at designing solutions

Adora explains that when a user asks for a specific feature, "usually what they're suggesting is not the best idea". Users are not product designers; they simply know they are frustrated.

2. The Request is actually a Symptom

When a user says, "Build Feature X," they are actually saying, "I have a blocked workflow." Adora argues you should not build the feature right away. Instead, you must investigate why they asked for it. The request is usually a signal that:

- You created a new problem for them while they were using the product

- There is a specific hurdle stopping them from paying you, and they think this feature will fix it

3. The Danger

If you take their request literally and just build the feature, you end up "piling on a bunch of features, which then hides the problem altogether". This leads to a cluttered, "Frankenstein" product that still doesn't solve the core issue.

What are customer segments?

1. Focus Before Building (The "Soccer Mom" Segment) Adora advises that before you even start building, you must identify your customer segments. While the "end game" is to have a product everyone uses, you cannot start there. You must "corner off a certain part of the customer base" so you can optimize specifically for them.

She suggests you might focus specifically on "teenage girls" or "soccer moms" to narrow your feature set and messaging

2. Unit Economics (The "Nashville vs. Czechoslovakia" Segment) Later in the lecture, she discusses segments in the context of Paid Growth and Cohort Analysis. She warns against aggregating all your data together because it hides the truth about whether your business is working. You must break down your Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) by segment.

She uses a hypothetical marketplace for country music. She notes that a user in Nashville, Tennessee, will likely have a much higher CLV than a user in Czechoslovakia. If you mix these two segments together, you won't know how much you can afford to spend on ads. You might overspend on the Czechoslovakia user or underspend on the Nashville user