In 2018, I found myself in Chicago for the GOTO Conference. I spent days immersed in talks about the future of software, surrounded by the sharpest minds in the industry. But the most transformative moment didn't happen in a keynote hall; it happened on a long, chilly walk along the pier near Lake Michigan.

Walking beside me was Joe Armstrong. To many, he is a titan, a co-designer of Erlang and a pioneer of fault-tolerant systems. His invention attributed to the current instant messaging technology (sms). To me, in that moment, he was like a mentor. He didn't talk about syntax; he talked about purpose. As we walked along the pier, he reminded me that coding began as a way to help people, not just a way to make money.

I left Chicago with those words ringing in my ears. I didn't have a world-changing algorithm yet, but I did have a very specific, very annoying problem.

The Problem No One Wants to Debug at 5:00 P.M. on a Friday

At my previous company, we lived and breathed Terraform. For the uninitiated, Terraform is the "master architect" of the cloud... it’s the tool that allows you to build and manage massive digital infrastructures through code. But it had a good fatal flaw: it moved too fast. And sometimes, the configuration that worked perfectly yesterday becomes a headache today.

The first time I truly understood the cost of Terraform version mismatch wasn’t during a dramatic outage or a big production incident.

It was worse than that.

It was Friday. 5:00 p.m. The kind of moment where your brain has already clocked out and your body is halfway out of the door. People were packing up. Someone was already talking about having drinks after work.

Then a coworker, the guy who sat next to me, pushed a Terraform change.

Nothing looked “wrong” at first until I pulled the branch, ran terraform plan, and Terraform responded with that cold, bureaucratic refusal that only developer tools can deliver: no plan, no progress, just an error that makes you feel like you’re the problem.

He had used a newer, incompatible Terraform version. The code worked on his machine because his Terraform binary understood the new syntax/state expectations. Mine didn’t. And our pipeline didn’t.

And because it was Friday at 5 p.m., the timing turned a normal mismatch into a hostage situation.

I remember thinking: This is going to be quick.

It wasn’t.

One “small” incompatibility turned into a chain reaction: upgrading here broke something there, fixing that revealed something else, and every attempt to “just make it work” multiplied the surface area of the mess. The deeper I went, the clearer it became: this wasn’t about the code. It was about tooling drift... everyone quietly running their own version of reality.

By the time I finally got it working, I was the only person in the office.

I spent my Friday evening doing what no one puts on a resume: untangling a version mismatch that could’ve been avoided if switching Terraform versions were effortless.

That night, the idea for tfswitch wasn’t theoretical anymore.

It was personal.

tfswitch

That’s how tfswitch was born: a lightweight way to switch between Terraform versions without ceremony.

Yes, while there were other tools that did something similar. But I wanted something different:

- Simple

- Minimal configuration

- Dirt easy to install

The very first version had about five features and that was intentional. I didn’t want a Swiss Army knife. I just wanted a sharp blade.

It was lean, fast, and did one thing perfectly. Almost immediately, the community noticed, and the feature requests started flooding in.

It is tempting to say "yes" to everyone. It feels like progress. But as the project grew, I realized I had to protect it from the Frankenstein Effect. If you sew every requested limb onto a project, you don't get a better product; you get a monster. You get a tool that is heavy, confusing, and ultimately breaks under its own weight.

When a user asks for a feature, they’re usually saying: “I have a problem you haven’t solved yet.”

I learned that when a user asks for a feature, they are really saying, "I have a problem you haven't solved yet." My job wasn't to build their specific request, but to find the simplest way to solve the root problem without breaking the soul of the tool.

The Frankenstein Warning: Don't build every feature users ask for. If you do, you get a "Frankenstein" product. Dig deeper: usually, when a user asks for a feature, they are actually saying, "I have a problem you haven't solved yet".

That philosophy shaped almost everything that came next.

Documentation Was My Real Growth Strategy

I quickly learned something humbling: building a tool is not the hard part.

Getting strangers to trust it is.

So I treated documentation like product.

And... to get people to trust a new tool, the "handshake" has to be perfect. I obsessed over the documentation. I didn't just write text; I created GIFs so users could see the tool in action instantly. I provided copy-paste commands to make the "time to value" less than ten seconds.

I also wrote a blog post on Medium and mentioned it on Twitter a few times. Nothing fancy. Just enough to help the project exist outside my laptop.

Then something happened that felt unreal.

The HashiCorp Moment

The turning point came when HashiCorp, the creators of Terraform officially recommended tfswitch at their global conference. Suddenly, my "little project" was a global utility. Downloads spiked into the millions. But with that success came a crushing weight: I was now the sole gatekeeper for a tool used by thousands of companies.

I begin to realize that this wasn’t just my side project anymore. People were going to depend on it. And dependency has a cost.

Nightmare maintenance

More usage meant more bug reports. More edge cases. More issues I couldn’t reproduce because they happened on a machine I’d never seen, in an environment I didn’t have, with constraints I never considered. And the truth is: I couldn’t keep up alone. So, I opened the doors.

I started letting others contribute features and fixes. I still acted as the gatekeeper for releases, but I knew gatekeeping alone doesn’t scale so I built a comprehensive test suite to protect the project from accidental breakage.

Still, the issues often outweighed the fixes. Not because contributors weren’t good but because maintaining a widely used tool is like bailing water out of a boat that keeps meeting bigger waves.

That’s when I realized the real bottleneck wasn’t code. It was help...

Building the “Help Me” Pipeline

I needed a system that made it easier for people to contribute even if they weren’t Golang experts.

If someone wanted to contribute, I wanted them to succeed without needing me to hold their hand.

I built a "Help Me" pipeline. I wrote exhaustive, step-by-step guides on how to clone the repo, set up the environment, and contribute code. I wanted to make it so easy to help that a developer with only a week of experience in the Go language could feel like a hero contributor. I stopped being a "coder" and started being a "community builder."

The goal was simple: make contributing easier.

And for a while, it worked... until life happened.

The Season I Couldn’t Do It Alone

About a year later, I got really, really busy. Job search, life shifts, the kind of weeks where you’re doing your best just to stay afloat. The project didn’t stop needing attention.

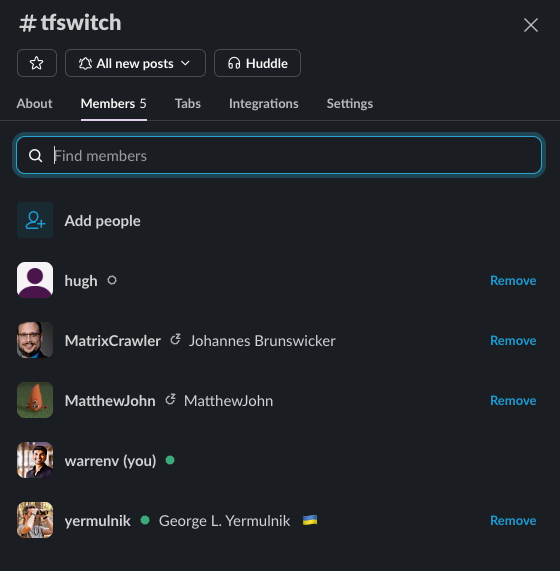

I needed a group of maintainers I trusted. A committee. A fellowship.

The Fellowship of the Code

In The Lord of the Rings, the Fellowship was a group of unlikely allies from different worlds, united by a single, heavy burden. I knew I couldn't carry the "One Ring" of this codebase alone anymore.

I reached out to a handful of contributors and asked if they’d help review and maintain the project.

And in my head, I started calling them the Fellowship: like The Fellowship of the Ring 😄. In Lord of the Rings, it isn’t about the journey looking heroic. It’s about carrying something heavy without dropping it.

To make collaboration real, we needed a home. We considered Discord, but we ended up using Slack. It gave us a shared space, and we hooked GitHub notifications right into the channel so whenever something happened (issues, PRs, discussions), it wasn’t trapped in one person’s inbox. More importantly: it created cadeance.

Code review became a shared responsibility. Most PRs needed at least two sets of eyes. Releases didn’t depend on one person having a perfect weekend.

We built a culture of accountability.

Shorten release cycles and tighten the feedback loop

Instead of waiting four weeks to release fixes, we put checks and automation in place so we could release or roll back, a version quickly, directly through GitHub, with confidence. I am no longer the bottleneck; the community is the engine.

That’s the part people don’t always see from the outside. They see “vX.Y.Z released.” They don’t see the systems behind it that keep the project from collapsing under its own popularity.

Twelve Million Journey

Today, tfswitch has seen 86 versions and over 12 million downloads. We’ve automated our release cycles so that we can deploy or rollback a fix with a single click, keeping the feedback loop as tight as possible.

One thing I have learn is that I didn’t do it alone.

I couldn’t have.

Two people I want to name explicitly: George L. Yermulnik and Matthew John - people I have never met in person, yet who helped carry this project forward. Yelmunick is from Ukraine and is the main person maintaining the software at the moment. I genuinely hope I get to meet him someday.

Because open source is a strange weird kind of friendship. When you build something worthy; strangers show up.

What I Learned (And What I’m Still Learning)

What I actually built was a lesson in responsibility.

Thanks for reading this far. If you want to keep following these types of stories, subscribe to my blog. There’s more to tell.